Advancing digital public infrastructure for social protection

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is increasingly recognized as an enabler of social progress. Foundational DPI building blocks – digital identification, payments and data exchange – allow public and private service providers to efficiently deliver digital services across a range of sectors. As efforts to build DPI gain pace, there is growing interest among social protection practitioners to develop a shared understanding of DPI and its potential to transform the delivery of social protection. Should the sector be actively engaged in leveraging DPI and related concepts to advance social protection? How can foundational DPI support social protection systems, and is there a need to develop complementary sectoral DPI specifically for social protection?

These questions were at the heart of a virtual workshop, convened by the Digital Convergence Initiative (DCI) and the Social Protection Inter-Agency Cooperation Board (SPIAC-B)’s Working Group on Digital Social Protection, which brought together key stakeholders to discuss the concept and practical applications of DPI for social protection. The meeting took place against the backdrop of considerable political momentum for the DPI agenda globally, with South Africa’s G20 Presidency emphasising the importance of DPI for countries’ long-term development.

The start of a dialogue on a sector-led DPI approach

The workshop, which was held on June 12, 2025, brought together representatives of multilateral organisations, development partners, and digital public goods, as well as social protection experts and researchers. Its objectives were threefold: first, to develop a joint understanding of DPI; second, to explore how DPI can be applied in social protection and how social protection applications, in turn, can advance the DPI ecosystem; and third, to assess what the social protection sector needs to do to leverage DPI in the future.

The workshop marked the start of a broad and structured dialogue between diverse organizations in the social protection space. Co-steered by DCI and SPIAC-B – leading international initiatives committed to the achievement of universal social protection – this process seeks to establish consensus around a sector-led and sector-owned DPI approach.

Why DPI matters for social protection

Workshop participants came from different starting points in terms of their familiarity with and understanding of DPI. Asked to share why the topic is relevant for social protection, many noted that DPI can unlock efficiency gains, allowing benefits and services to be provided more quickly and at scale. It was also emphasized that DPI can connect more data and services, making delivery more integrated and responsive. Others pointed to its potential to reduce errors and fraud, and to increase transparency in the delivery of benefits and services. DPI is also seen as a force for greater inclusion, as it enables social protection programs to better reach beneficiaries. Participants underlined the risk that DPI can generate exclusions if it is not carefully designed, thereby highlighting the importance of safeguards in DPI implementation.

Towards a shared understanding of DPI

At the workshop, representatives from the United Nations Office for Digital and Emerging Technologies and from the World Bank introduced the concept of DPI and its relevance for development.

Countries around the world have been making great advances in the digitalization of public services in recent years. Frequently, however, digitalization takes place in siloes. Governments create separate digital systems for each sector and department, duplicating efforts at every level, from user interfaces to backend databases. This fragmented approach makes it harder for systems to work together, drives up costs, and slows down innovation and scaling.

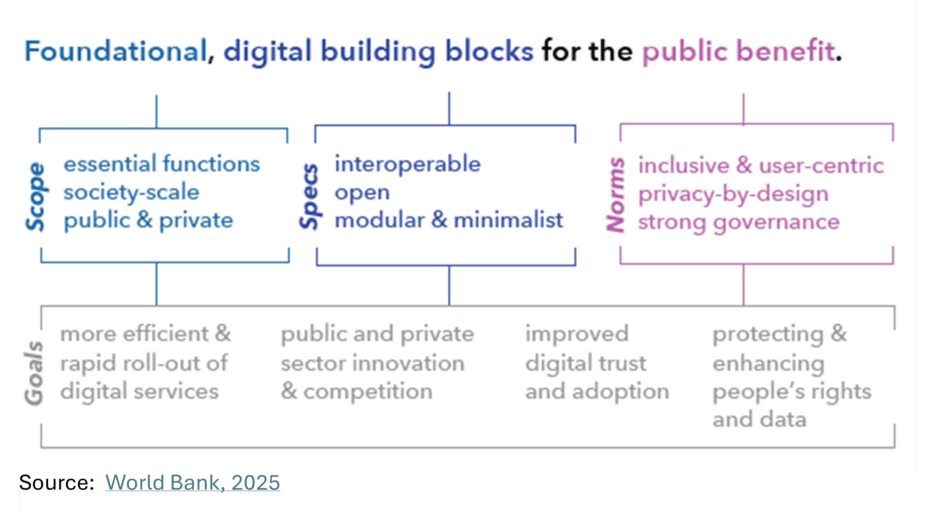

By contrast, governments that invest in DPI are shifting to shared digital tools and platforms that can be used across sectors. The World Bank defines DPI as ‘foundational, digital building blocks for the public benefit’ (see figure). These building blocks offer essential digital functions, such as digital identification, digital payments and secure data exchange, which can be used society-wide, i.e. they are non-sectoral. DPI systems are guided by the principles of inclusion, openness, modularity, inclusivity, user-centricity, privacy-by-design and strong governance.

Interoperable DPI services work together as a ‘digital stack.’ Public and private providers from a wide variety of sectors can draw upon foundational DPI components to facilitate efficient and secure program delivery. Moreover, they help to streamline digital efforts and foster interoperable, inclusive digital systems.

How sectoral DPIs can enhance digital transformation of social protection

Social protection is a leading use case for foundational DPI. Social protection programs which leverage foundational DPI can achieve greater reach and deliver services more efficiently, ensuring that people entitled to support receive it in a timely manner.

An input from the Global Alliances for Social Protection program at GIZ looked at DPIs through a sectoral lens, considering the experiences of sectoral DPIs in health and agriculture. In these cases, specific sectoral DPIs both complement and leverage foundational DPI to unlock new opportunities. The development of these sectoral DPIs has been informed by use case and user perspectives. In the health sector, for example, user journeys have been used to identify components of health DPIs which would enable a range of health applications. In agriculture, both country-specific and global initiatives are shaping how DPI is being developed for the sector. A common theme across sectors is the role of Digital Public Goods (DPGs) as a basis for DPI. These include open-source software, open standards, and open data, which countries can adapt and implement as part of their DPI strategies. In social protection, DCI interoperability standards are one example of DPGs that can support data exchange and, when implemented as part of a country’s DPI, make programs more connected and effective.

The social protection sector relies upon core systems, such as registries and grievance redressal mechanisms, to address specific needs within the social protection delivery chain. Developing these as sectoral DPIs could help make the digital transformation of social protection systems even more efficient and inclusive by minimizing duplications, reducing administrative costs, and enhancing coverage.

In practice, this means treating these core systems as shared digital building blocks that can be reused across programs, rather than as isolated IT projects. A social registry, for example, can be designed as a dynamic, interoperable platform that multiple schemes draw on, while grievance redress or case management systems can be set up with common standards, so feedback and appeals are handled consistently. Linking these components to foundational DPI, such as digital ID and payment systems, makes it easier to verify beneficiaries, deliver transfers on time, and maintain transparency. By building sectoral DPI using open-source solutions, governments might gain flexibility to scale services, improve coordination, and extend social protection delivery.

Leveraging DPI for social protection: key takeaways and next steps

The workshop ended with a discussion session in which participants validated the questions the workshop set out to explore. Overall, they were optimistic about the prospects of advancing DPI for social protection and endorsed a continuation of the dialogue towards the establishment of a consensus position.

It was noted that the DPI concept has evolved as a non-sector-specific ‘whole of government’ approach, and that foundational DPIs do not necessarily address all needs or meet the social protection sector’s full requirements. DPI needs to be taken one step further to be leveraged for the social protection context. The principles which govern foundational DPIs can be applied in the social protection sector to develop complementary, sectoral DPIs.

A range of additional themes and questions emerged from the discussion. Among them:

- What are the foundational DPIs for social protection?

- Who maintains Digital Public Infrastructure? What models exist for the governance for DPI maintenance?

- To what extent can the social protection sector in any county operate independently of choices being made at the central level, for example, by ministries of digital transformation?

- What practical support do country-level social protection stakeholders need to navigate the complex choices they face in implementing DPI for social protection?

- What criteria should be used to assess DPI use in social protection?

- Although the government-led foundational DPI gets the most attention, some countries are making other choices in building DPI. How can they access guidance and support if needed?

- How does social protection benefit the broader DPI ecosystem? Can social protection’s commitment to reaching vulnerable populations help to make DPI building blocks more robust and inclusive?

The next stage in this dialogue process will be the development of an inception report which grapples with these and other questions. Get in touch with us at contact@spdci.org if you are interested in collaborating on the development of a shared vision for DPI in social protection.

Additional resources

- The DPI Approach: A Playbook | United Nations Development Programme

- Leveraging Digital Public Infrastructure for building inclusive social protection systems

- Digital Public Infrastructure for Health

Author: Karen Birdsall